Nothing jump-starts a legal mind like a brand new case. As you read the Complaint for the first time, the former law student in you begins issue-spotting automatically and fires off a barrage of questions:

What’s the jurisdictional basis? Is it a vessel? Seaman or Longshoreman? Are punitive damages available?

Not to be outdone, the seasoned litigator in you adds to the growing pile:

When are responsive pleadings due? Who is opposing counsel? Who’s the judge? Didn’t we just handle a similar case?

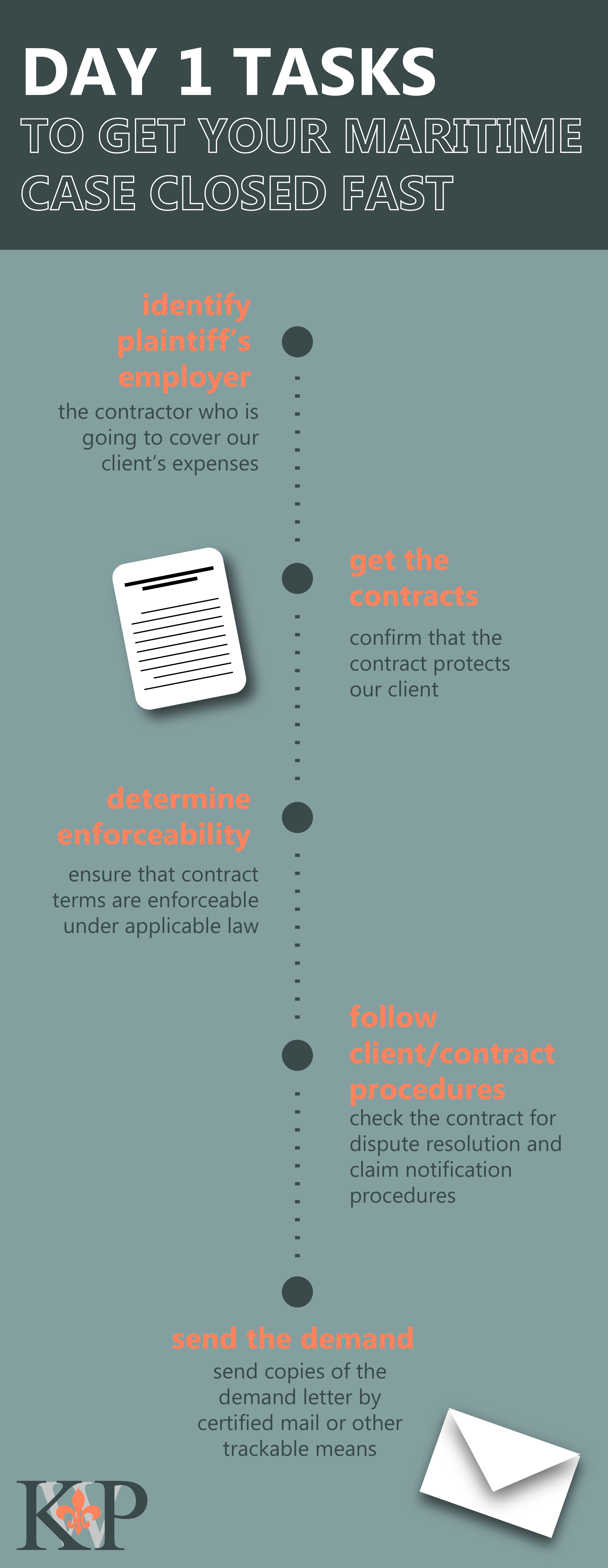

Sometimes it seems hard to know where to begin. But the answer is pretty simple—begin at the end. There is nothing more valuable to defense clients than a quick win, and attorneys should strive to develop a reputation for ending litigation or delivering file closure before it’s expected. With rare exception, contractual indemnity is the fastest and least expensive way to get a new maritime file off of a client’s desk. Here are steps we strive to complete on Day 1 of a new maritime case.

Identify Plaintiff’s Employer

First, we want to identify our target—the contractor who is going to cover every dime of our client’s expense. Contracts for offshore work commonly require an employer to defend and indemnify those who are sued by its employees, so plaintiff’s employer is usually the first and best option. In Jones Act cases, the employer will always be a named defendant and the employment relationship will be clear from the allegations in the Complaint. In the event the employer is not identified in the Complaint, we pick up the phone and ask plaintiff’s counsel. Our client’s time is money, and it should not be wasted waiting for formal discovery on non-controversial matters.

Get the Contracts

Next, we get the signed documents. On the day a new file is assigned, we request copies of the relevant contracts and work orders between the client and the plaintiff’s employer. Our efficiency-focused maritime clients understand our goals and provide these contracts with the new case assignment before we even have to ask.

Master service agreements and vessel charters can be quite complex and the risk allocation, indemnity, and insurance provisions are thoroughly and carefully reviewed. We confirm that the contract language identifies the client as an indemnitee and that it contains specific language allowing the indemnitee to be indemnified for its own negligence.1 If our client did not contract with the plaintiff’s employer, we request and examine its agreements with other named defendants in the suit. Oftentimes, contractual indemnity and defense obligations “pass through” other entities and provide coverage to our clients. By maintaining familiarity with our clients’ contract language, we can expedite the analysis.

Determine Enforceability

Once we’ve confirmed that our client is owed defense and indemnity pursuant to the contract terms, we need to ensure that those terms are enforceable under applicable law. Our seasoned maritime attorneys are well-versed in choice-of-law analysis, state anti-indemnification statutes and, importantly, the exceptions thereto.2

Follow Client/Contract Procedures

Assuming the contract terms are enforceable, we check the contract for dispute resolution and claim notification procedures. We strive to recommend the next steps to our clients in every status report and, in this situation, those steps must conform to contract requirements.

Some agreements require notices to be sent to particular individuals or office addresses. Others allow the indemnitor to recover attorneys’ fees and costs if the indemnitee fails to employ alternative dispute resolution before filing a cross-claim or separate lawsuit for defense and indemnity. We avoid pitfalls by being accustomed to the terrain and our clients rest assured that we will take no action on this issue without specific authorization.

Finally, we consider our client’s internal procedures and preferences. Some companies’ legal departments require approval from their business units before a formal tender letter can be issued to a contractor. Some clients wish to issue tender letters directly, while others prefer to present them on our firm letterhead. Some clients prefer lengthy demand letters that attach the Complaint and all contract documents, along with a full legal analysis. Such letters project strength because they imply that formal legal action is a mere “cut-n-paste” away. Other clients see lengthy demand letters as giving away too much information, preferring instead simple demands merely attaching the Complaint and referencing a contract number. We seek out our clients’ individual preferences to deliver precisely what they want when they want it.

Send the Demand

The best practice is to send copies of the demand letter by certified mail or other trackable means to (1) the entity’s registered agent for service of process; (2) the notification addressee identified in the contract; and, (3) the entity’s counsel of record in the underlying litigation (if applicable). This increases the likelihood of a prompt response, which can save our client time and money.

Our clients may not always remember opening a new case file with multi-million dollar exposure and a litigation budget of hundreds of thousands of dollars. We only want them to remember how Kuchler Polk Weiner, LLC closed it, at little or no cost to the company, in a matter of weeks.

— Mark E. Best

- Indemnification for an indemnitee’s own negligence must be “clearly and unequivocally expressed.” An indemnification of “any and all claims” standing alone is not sufficient to indemnify the indemnitee for its own negligence. Seal Offshore, Inc. v. Am. Standard, Inc., 736 F.2d 1078, 1081 (5th Cir.1984) (citations omitted).

- The number of potential fact patterns, legal issues, pitfalls and outcomes of this analysis are too numerous to discuss in this space, and may be the subject of future posts.